ON THE HIDDEN COSTS OF NFTS

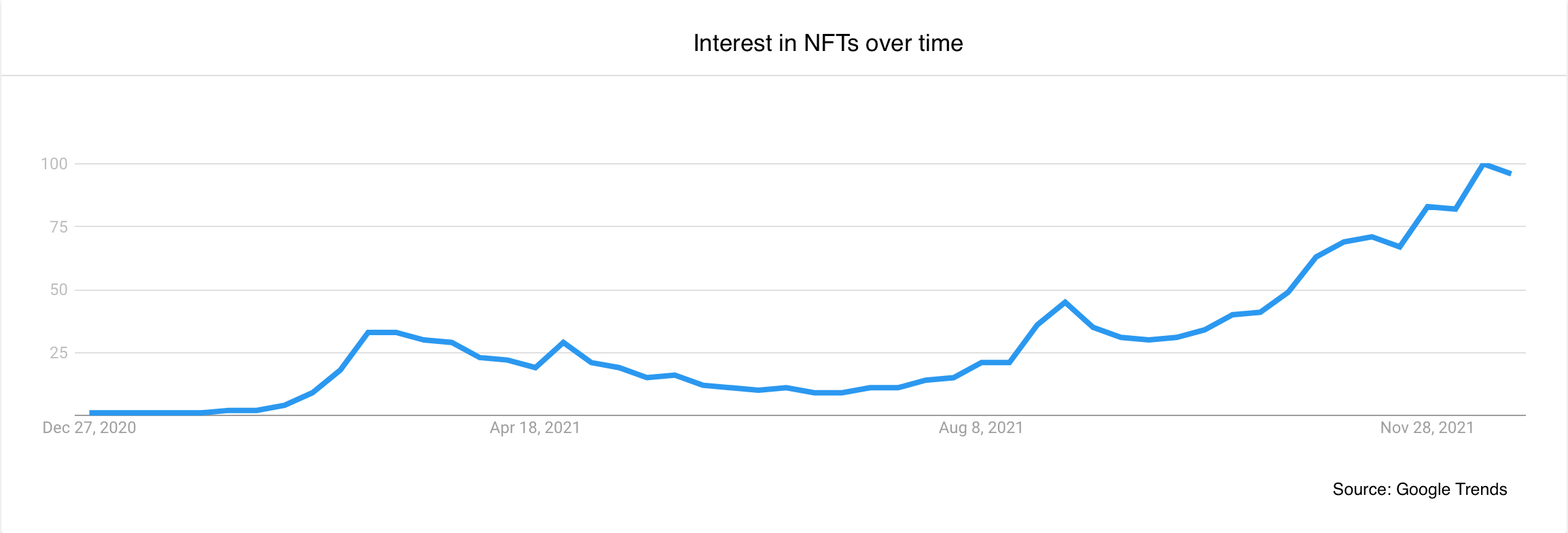

Non-fungible tokens - NFTs - are the hot topic when it comes to the modern digital art market. Hot as in trendy, and hot as in a significant driver for global warming.

NFTs are unique files that are able to verify ownership of a work of digital art. The major marketplaces for NFT art conduct their sales through Ethereum, a decentralised blockchain network, which maintains a secure record of cryptocurrency and NFT transactions, and is upheld through a process called mining. This system involves a network of computers that use advanced cryptography to decide whether transactions are valid and to keep blockchain records coherent. Running all this computational power uses energy on the scale of a small country and, while translating this energy consumption to carbon emissions is difficult, the sheer scale of energy use should get us thinking - what’s the use of allocating any at all for crypto art?

We’ve seen the way digital art has been pirated in the past and we all remember the ‘You wouldn’t steal a car’ anti-piracy ad, but that didn’t really stop people from downloading movies and music albums, did it?

So what is the ultimate point of owning an NFT? While anyone can see and easily screenshot the world’s first tweet (which was sold for 2.9 million USD), they would have to purchase the individual, impossible-to-pirate, limited-edition NFT version if they wanted the distinction of owning the original, collectable version. These ownership certificates usually give buyers limited rights to display the digital artwork they represent, but in reality these are no more than bragging rights.

The world’s first tweet (complementary)

People might argue that if someone is willing to pay that much money for an ownership token then that’s fair game and nobody else’s business. But if this NFT frenzy is feeding on a resource-heavy technology for the sake of questionable art ownership, doesn’t it concern us all? When an NFT is sold there is a seamless transaction in the digital world that translates to a very real and large energy spend in the physical world, and because of hype-driven markets, these artworks are then re-sold over and over again - a trend not predicted to stop anytime soon.

The stories of artists becoming millionaires overnight (which are far rarer than the internet wants you to believe), the ethical and environmental concerns behind NFTs and all the current hype around them make these ‘digital receipts’ as divisive as they are popular. But where do they add value in this world besides to someone’s bank account?

Take Brian Eno, a ‘would be’ perfect artist for the NFT era, having spent decades intertwining technology and its social implications in his practice as well as building a huge fan base along the way. But instead of joining the craze and effortlessly banking a few million pounds, Eno has decided to keep away from this market, convinced NFTs are pointless as an artistic move and craven as a financial one:

“NFTs seem to me just a way for artists to get a little piece of the action from global capitalism, our own cute little version of financialization. How sweet — now artists can become little capitalist assholes as well.”

Brian Eno for the Crypto Syllabus

The discussion on NFTs is far from over, and while NFTs didn’t have all this ethical and environmental baggage attached to them back when they first started in 2014, their quick rise to internet fame brings a lot of questions that demand answers before artists blindly jump in to get a piece of the $$$ action.

ON THE HIDDEN POLITICS OF ART INSTITUTIONS

Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum? (1989), Guerilla Girls

The museum is a place to experience art, explore various ways of crafting and learn new things through the reading of artworks. This is especially the case with political art – providing an insight into the making and unmaking of the world. However, the hidden processes of a museum rarely come to the surface.

In the late 1960s, many artists started to investigate and question these unseen affiliations in their practice. These were the beginnings of the art movement Institutional Critique. The movement included many artists, such as Hans Haacke, Daniel Burren and Marcel Broodthaers. They began to challenge the romanticised perceptions of the museum as solely a place to experience art. Institutional Critique aims to uncover the engagements of the museums' sponsors and individuals involved in the institutions' governance. As a direct consequence, art considered Institutional Critique has been repeatedly subject to censorship. These acts of silencing further reveal the power dynamics behind the drawn curtains of the museum.

This becomes apparent in Haacke's Manet-PROJEKT'74 (1974), which he created for the PROJEKT'74 exhibition at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum. For this installation, he mapped the provenance of Manet's 'Bunch of Asparagus' (1880) on ten panels – identifying the previous owners by name as well as their social and economic engagements. The last panel of Haacke's installation is dedicated to Hermann Joseph Abs – and reveals his crucial role during the Second World War as a financial advisor of the Nazis. Abs also became the Spokesman of the Board of Managing Directors of the 'Deutsche Bank' from 1957 to 1967 and was subsequently chairman of the Supervisory Board until 1976. At the time of the PROJEKT'74 exhibition, Abs was the chairman of the board of trustees of the 'Wallraf-Richartz-Museum'. Presenting these precarious ties between a former NS-supporter and the museum led the exhibition's curatorial team to censor Haacke's project – consequently not including it in the show.

Manet-PROJEKT’74 (1974), Hans Haacke, installation view at Paul Maenz Gallery, Cologne in 1974

The Deutsche Bank has a history of supporting Nazis AND the arts, made apparent by its solely for art purposes, dedicated website. With their 'art programme', they have funded (and continue to fund) various awards and support numerous institutions, such as Tate. However, their motto; "Art builds. Art questions. Art transcends borders. Art works.", does not deceive us – instead, it reveals a pathetic attempt to polish their image and hide the morally questionable aspect of their operations and processes (such as being one of the main European Banks profiting from tax havens).

One of the most famous art organisations in the UK is Tate; an exempt charity and non-governmental institution governed by a board of trustees, with the UK Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) being its main sponsor. Tate also offers corporate partnerships and memberships, with their corporate partners including, among others, the Bank of America, Hyundai, BMW and, as previously mentioned, Deutsche Bank.

Tate's galleries attract millions of visitors, which would not be possible without such sponsors. Focusing on African and Asian art, it could be argued that the partnership between Tate and Deutsche Bank is an endeavour of great importance in facilitating exposure through such exhibitions. However, while the bank is profiting from being associated with such an internationally renowned art institution, Tate is not. Demonstrating that art can be just another capitalist commodity, which is hardly news – but still doesn't sit quite right. Especially when the motivation behind an artwork is to question and critique social and political issues – of which, corporate sponsors, like the Deutsche Bank, follow a completely different philosophy – often contributing to or being the very reason for the problems in the first place.

Institutional critique has become more 'mainstream,' with artworks silenced less and less - readily exhibited in the institutions they were once created to critique. Furthermore, it has become a frequently discussed topic among curators and critics. However, this increasingly open engagement creates an ambivalence - since institutions are still dependent on funding and support by controversial stakeholders and corporations – essentially tainting the institution itself.

The questions remain. How is the artist and their work 'compromised' by such partnerships? Or is the platform, the reach, an institution provides of greater importance? Principles are naturally important but don't pay the rent. So how can practitioners' control in which context their artwork is presented after they sell their work?

For Haacke the 'Artists' Reserved Sales and Transfer Agreement', also referred to as 'Artist's' Contract', provided a solution. Originally created in 1971 by Seth Siegelaub – a curator of conceptual art – and lawyer Robert Projansky, the contract is an attempt to protect the integrity of artworks by allowing the artist the right to decide in which context it is exhibited after a collector or a gallery has purchased it. Furthermore, in case of a profitable resale, the contract obliges the seller to pay the artist 15% of the profit - not making it very popular among collectors. However, the agreement allows artists like Haacke to stay in control – previously enabling him to veto the inclusion of his work in a public exhibition – sponsored by a corporation he did not want 'to be associated with'.

The ‘Artist’s contract’ may be a good first step to protect the integrity of an artwork after it is sold - allowing the artist to keep some control in the face of institutions. In the long run, perhaps what is needed is a more radical change - proposing a new relationship (or a divesting of relationships) between the artist and the institution - and asking ourselves the question; what does art look like beyond the museum?

ON SECURITY

The Main Concepts of Security in the Modern Age - from ‘The Security Principle: From Serenity to Regulation’ by Frédéric Gros

This month marks twenty years since 9/11 - an epoch after which notions of ‘security' (particularly national security) have shifted significantly both politically and culturally - when collective grief was exploited to expand state powers (both in the US and Europe) and justify imperialist foreign policy in the Middle East.

With the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan now ‘complete’, where do the crimes and violence enacted in the name of national security sit? And how have wider notions of security provided the basis for the expansion of state power and systems of control that continue now?

In his book ‘The Security Principle’ [nb. here’s our book review - you can skip the first two chapters, tbh bit wanky. Third chapter is where it’s at, and fourth is a ~ride~ when read during a pandemic ….¯\_(ツ)_/¯. fin] Frédéric Gros sets out that we “think of the state as the bearer of the monopoly of the forces of security: it is the state that must maintain public order, it is the state that ought to protect us against terrorist threats, it is the state that has to implement health policies adequate to dealing with the threat of epidemics, and so on”. (lol at that last bit amirite?)

Cultural ideas of security in the “modern era” have steadily moved away from that of serenity or the guarantee of one’s fundamental rights. Instead, security is more and more invoked in the name of public order and the safety (and preservation) of the state itself rather than its people. For instance: national, military and police security take precedence over the millions of adults and children that experienced food ‘insecurity’ (read: food poverty) during the pandemic.

This priority further surfaces in a number of ways, including intrusive surveillance and the expansion of the carceral estate. Security in this sense is removed from any inherent stability; instead it is a constantly moving target, its continuity relying on perpetual new inputs and provoking new reactions. Sold as the antidote to the fear and instability purposefully instilled by the state, security is positioned as a commodity, and as with all commodities, it is then capitalised, privatised, and outsourced.

While contradictory to the model of the state as the guarantor, this outsourcing is a practise prevalent across the multiple dimensions of security, such as the presence of defence companies and private military personnel in military security; or the expansion of surveillance, through private tech and domestic doorbell cameras in police security. Outsourcing allows the state to remove itself from accountability and obfuscate the modes and methods used in the pursuit of security.

Gros concludes that “Neoliberal regimes are doomed to become police states” - in order to contain the “explosions of misery” of the dispossessed and marginalised pushed further into inequality. The apparatus of security put in place by those in power is then self perpetuating, its implementation not only widening these already vast inequalities, but proclaiming to guard against the instability and fear instilled by the securitarian state itself.

ON COMMUNITY BUILDING

We are thrilled to officially announce the four practitioners-in-residence of RAKE Community 2021

The idea to facilitate some kind of ongoing, fluid community-based project came along at the same time as the idea to form a collective - before we had any idea what to call anything or how to set the two apart. In addition to pursuing our own collaborative practice, which has a strong focus and agenda, we have always wanted to work towards making it easier for artists, writers and anyone else who may not have been as lucky as us (who practically fell into each other’s arms begging to work together after a few pub sessions) in finding the right people, in the right place, at the right time, to team up with on creative research projects. Although RAKE Collective & RAKE Community are separate initiatives with distinct rationales, the same motivations are in place: to facilitate collaboration, skill-sharing, communal learning and mutual growth.

Loneliness increased significantly during the pandemic - and the art world can be particularly lonely, with practitioners often needing physical and emotional space to work. This, combined with the unnecessary but pervasive element of competition (and the ridiculous image of the lone genius) has made the need for creative collaboration all the more relevant. RAKE Community was launched off the back of pandemic-induced disconnect and our feeling that now was a better time than ever to try out a ‘test-run’ of something we’d been thinking about since forming RAKE. Through the initial programme in 2020 we were lucky enough to build genuine relationships with some incredible practitioners who we still regularly catch up with, trade feedback on creative projects and generally help each other out - all without having to navigate a single forced networking event or hang out sleazily at gallery openings twiddling our thumbs and waiting for ‘someone important’ to finally ask us what the hell we want.

Alongside a yearly ‘official’ programme taking place over a set period of time with participants selected through open calls, we dream of RAKE Community becoming an ever-changing and growing experimental space/ place/ concept/ project where practitioners can find what they need and share what they can: a year of fascinating Instagram takeovers and the launch of the RAKE Community online workspace preceded this year’s programme. And now we are super excited to officially announce the four selected participants of RAKE Community 2021: Practitioners-in-Residence! You may have already been watching the brilliant research of Meredith Morran, August’s practitioner-in-residence, unfold over the past few weeks. They’ve been engaging with Instagram - aka ‘baby’ - to expose the inner workings of social media sites and disrupt the standard user experience, while testing and toying with the limits of baby’s algorithm. More on Meredith’s research below.

Coming up in September is Self_Saboteur, who will be showcasing the curatorial process of choosing artworks to feature in a Race & Disability Zine Anthology. By exploring the intersections of race and disability through investigating narratives and stories in mainstream media, the project aims to uncover ideas around invisibility and marginalization. In October, Konstantina Mavridou will be asking how humanity decides which problem-questions are the ones to solve, especially before innovative technology is produced. Her residency will research the foundations and axioms we use to set the actual questions and various hypotheses to be researched upon, humanity’s needs to be covered through new technological inventions, as well as the directions we set in order to lead into new scientific discoveries. Lastly is Catarina Rodrigues who, throughout November, will be investigating the ritualistic performance of neural network algorithms and how rituals themselves can be seen as forms of computation in their ability to transmit information and to create networks. We absolutely cannot wait to see their research develop, and are keeping our eyes peeled for some possible collaborative extensions in December!

RAKE’s motivation to push the boundaries of storytelling and democratise research comes hand in hand with a responsibility to give back to the community that has shaped our practice. So - here’s to the family members who made the food and manned the doors at our launch exhibition; the partners who coded our websites & trekked down to Brighton on their days off to install our Photo Fringe show; the friends, flatmates and coursemates who’ve cooked for us & encouraged us & pulled strings to help us out; the parents who’ve hosted us & fed us; the tutors who challenged our ways of thinking & flipped our practices on their heads; the siblings who‘ve fronted the cash for countless wine-dashes during particularly intense meetings; and the wonderful people, from professional practitioners and creative directors to community organisers and facilitators, we’ve met through RAKE over the last 20 months who continue to champion, motivate and educate us. If RAKE Community can, in any way, help others - as we’ve been helped by others - we’ll be happy.

fun fact: the one and only Beyoncé’s Lemonade album credited 72 writers

ON SURVEILLANCE: NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH

Screenshots of different features of the police portal for the Amazon Ring doorbell network.

Neighbourhood social media apps such as Nextdoor or Neighbors (by Amazon Ring) promise a feeling of safety: people are able to share their concerns and see what others report as suspicious in their local area. By installing these apps anyone can easily share footage from home security cameras and, at the same time, have access to a feed of footage neighbours have shared.

Despite reports showing that crime has fallen steadily in the last decade the popularity of such apps is increasing; fitting into the category of fear-based social media, these apps contribute to a false sense that danger is on the rise. And for the companies behind them, "fear is good for business” as growing fearfulness leads to more people thinking they need surveillance devices in their house in order to be safe.

These apps place power in the individual’s hands to determine whether someone does or does not belong in a community, and as a result introduce bias and reinforce unfair policing, which can then potentially feed into a vicious cycle of fear and violence. Racial profiling is common, with a large majority of those reported as “Suspicious” being people of colour. If this technology is helping perpetuate stereotypes, is it making your neighbourhood safer - or just more racist?

This illusion of the rise of criminality promotes a falsified narrative, one the police have conveniently used to push surveillance equipment into people’s homes and makes it easier for police to request footage in bulk, sometimes cutting corners instead of getting warrants. In the US, all but two states now have police participating in Amazon’s Ring network, and in the UK the tech giant has given the recording devices to at least four forces to pass on to residents. At least five other forces have promoted the all-seeing doorbells via money-off vouchers or discount codes, and others are currently in talks with Ring.

When even Amazon employees say that “[t]he deployment of connected home security cameras that allow footage to be queried centrally are simply not compatible with a free society”, we have to ask ourselves, how much surveillance is enough until we’re all safe according to the police? It seems they can’t get enough eyes on the streets; London, for example, is already the 3rd most surveilled city in the world with almost 75 CCTV cameras for every 1,000 people, and yet the Met has received a £243,000 sponsorship from Amazon to deploy 1,000 Ring cameras in the capital. Do we really need more cameras? Following us from the moment we set foot outside our front doors? Connected to police databases? The collection of more and more data on us all does not necessarily mean better outcomes solving cases - but it does mean harm to a free society while it normalises mass surveillance.

Expanding the surveillance network to put police eyes in people’s peepholes blurs the lines between public and private spaces. Gathering this sort of data in bulk ‘just in case’ something of importance was captured directly affects our right to privacy from the moment we step out of our house. Our right to protest, our ability to freely criticise the government and express dissenting ideas, even our personal safety; the very thing most individuals are trying to protect when purchasing these devices, is then threatened when we unwittingly turn our neighbour or ourselves into the eye of the state.

ON VIRTUAL EXHIBITIONS

Our virtual exhibition ‘Where There Were Once Walls’ in the planning process in July 2020

In an article published by the Guardian last year, writer Laura Feinstein describes the COVID-induced surge of virtual exhibitions as the ‘beginning of a new era’. She explains how numerous museums, galleries and cultural institutions were forced to adapt to the social distancing rules and stay-at-home guidelines. Alternatives like attending artist talks on Zoom and experiencing exhibitions through virtual reality became an everyday part of our cultural programme during lockdown. But how has it changed our response to shows, and what are the benefits and disadvantages of exhibiting online?

About a year ago, we started the process of planning our own virtual exhibition, ‘Where There Were Once Walls’. Using a platform called ‘Kunstmatrix’ (which none of us ever managed to pronounce correctly other than, surprise surprise, Vera), we began to map out the different works created by the four pairs taking part in RAKE Community, alongside new components of our project ‘We May Meet One Day’. While in the beginning this was merely an alternative to an ‘in real life’ exhibition, the virtual exhibition provided us with various possibilities which a physical show could not have.

The creating and curating of the online space was initially abstract, fiddly, and annoying. After a couple of weeks the process became more straightforward, and the positive aspects of exhibiting virtually became increasingly apparent. In the previous material exhibitions that we’ve had, as a collective and as individuals, cost considerations, concerning the scale of artworks and other elements included, have always been a limiting factor. However, shouldn’t scale be a conceptual decision serving the artwork as opposed to one restricted by our savings? The answer is yes and no. Obviously, the artwork should be presented in the most fitting and conceptually relevant way; but at the end of the day we still need to pay rent, so...

In creating the virtual exhibition, the question, or rather the pressure, of cost was no longer relevant. Our chosen virtual room encouraged us to experiment with scale - it allowed us to ‘install’ massive wallpapers and extensive wall texts - which would not have been feasible for us in an actual space.

Virtual exhibitions generally lure with the promise of accessibility - offering artists the potential to reach an audience all over the world is undoubtedly alluring, and as a viewer, being able to view exhibitions from home, generally for free, even more so. However, its simplified accessibility also invokes false pretences of making it more accessible for everyone. In a recent piece for BJP, Jamila Prowse reminds us that “remote access alone does not ensure that disabled communities can easily navigate and engage with a gallery’s output”, while highlighting the fact that virtual exhibitions during the pandemic have still been almost exclusively built for able-bodied and neurotypical people.

Overall, exhibiting online can be a great opportunity and has provided many with much needed cultural stimulation during lockdown. ‘Where There Were Once Walls’ introduced us to the numerous perks of exhibiting online and we will certainly make use of such platforms again to present our work in the future. However, we as artists, along with galleries, museums and cultural institutions worldwide, must work towards creating a vastly improved and truly accessible art experience.

ON THE ONLINE SPACE

From The Internet Map, a bi-dimensional presentation of links between websites on the Internet.

In many ways the collective itself and our work has evolved since our launch, and particularly over the last year, with the online - and while we may have envisaged how these spaces would practically facilitate our work, we did not anticipate how intrinsically linked they would be to the subjects we investigate.

Even prior to the pandemic, to some extent RAKE worked remotely; both the first iteration of We May Meet One Day and our launch exhibition were largely planned online, across different countries. The majority of our audience has been built through social media and digital outreach, and RAKE Community 2020 would have never been possible without the connectivity available through the internet; allowing us to bring together participants across the globe, collaborate remotely, and virtually exhibit in the middle of a pandemic.

The online space has also, in the context of the past year, become a lifeline for many, keeping friends and families connected, and making it possible (and more bearable) for the majority to stay indoors through multiple lockdowns. But there are palpable dangers to this ease of connection, and the constant presence and availability of others.

Within our first project, we explored how this online space is the ideal environment for far-right recruiters to operate. Perpetual connectivity gives recruiters unique advantages; the ability to target individuals at any time, to be a constant presence in their lives, to send misinformation and propaganda directly into their homes, and to do so anonymously.

This may be even more prevalent now, where lockdowns and stay at home orders have isolated already vulnerable individuals, making them ripe for online recruitment and abuse. And this constant connectivity combined with the extreme pressure of a global pandemic and simple excess of time has allowed thousands to be drawn into complex misinformation campaigns, causing very real harm, often to already marginalised groups.

Online spaces can feel in many ways isolated from reality, echo chambers in which information propagates, and consequences aren’t always apparent. The lines between virtual and real become blurred; and in the case of far right recruitment, violent language and ever more extreme incitements become self-perpetuating.

The ubiquity of the internet in all our lives, has far reaching ramifications - to privacy, freedoms and even our individual safety. But it can also be a place to build communities, organise mutual aid, and find comfort; a place to uncover injustices, hold power to account and form global movements.

This duality of the online space is really an indication of its reality. Technology and the internet are integrated into nearly everything we do, and these spaces now exist as extensions of the real world, sustaining and recreating the complexities of life, society and culture.

ON DATA

Counter of average amount spend by the police in England and Wales since the beginning of the tax year

Our project We May Meet One Day (WMMOD) was based on data leaked for the purpose of public scrutiny, dumped online by an anonymous user who published the entire contents of the defunct neo-Nazi forum Iron March; exposing the personal information of more than 1,200 members, including individual IP addresses and locations, and - in some cases- their real names. The amount of information and the geographic reach of the forum allowed for a wide view of the movement and gave insight into how the far-right is mobilising globally. And because it was open, the public was able to come together to undertake a crowdsourced investigation, presenting an opportunity for anyone to engage with the data and search for patterns. This volume of data also aided in making individual arrests, such as the British police officer recently convictedof belonging to the extremist group National Action, who was found to be an active member of Iron March.

Although most users are not likely to use their real names or provide real contact details, investigators are presented with a myriad of new tools and information with which to identify people. In fact there’s a lot of damage that one can do with ‘publicly available information’ - data that we all simply put out into the world while exerting our right to communicate over what should be a more democratic world wide web. It’s important then to make a distinction between Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) and Social Media Intelligence (SOCMINT). OSINT is intelligence collected from publicly available sources, including the internet, newspapers, radio, television, government reports and professional and academic literature. While SOCMINT can be defined as “the analytical exploitation of information available on social media networks”.

A data visualisation of the frequency of different letter combinations in this months text

The overwhelming volume and variety of digital information posted to social media everyday is made possible through the growing number of mobile devices, sensors and tracking tools ever present in our pockets. Would you mind if, every time you posted a comment on Twitter, Facebook or another social media platform, it was logged by the police? It’s publicly available information, does that mean it’s fair game? It is arguable that a tweet is not private because you cannot control its audience. However, that does not automatically make it public, or within the purview of the police. SOCMINT does not easily fit into either the category of public or private. We can argue that it is instead a pseudo-private space, where there is an expectation of privacy from the state. Still we know social media is being used by the UK government to track asylum seekers, threatening their access to social benefits, and by police to target people attending protests.

Take action against the spying on asylum seekers via Privacy International

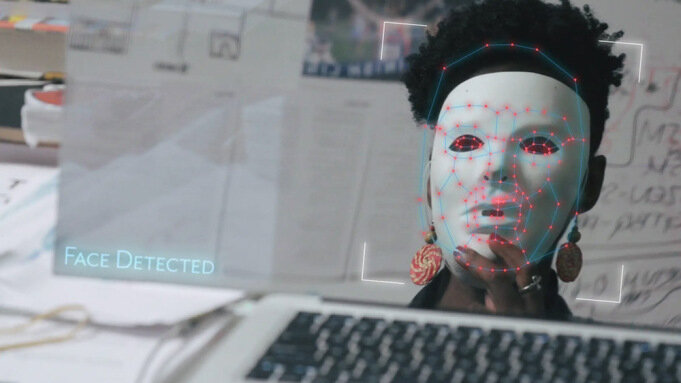

On another front, companies are abusing SOCMINT too. Clearview AI - whose CEO is known to be connected to the far right - and its cousin company Pimeyes have built huge databases for global facial recognition systems by collecting our faces from social media. This technology in particular risks becoming systematically weaponised against marginalised communities, while most of Clearviews’ clients are law enforcement agencies all around the world. As more studies emerge confirming that machines perpetuate existing biases while benefiting from a false sense of objectivity and neutrality, it is important to recognise that these technologies need scrutiny. As computer scientist and digital activist Joy Buolamwini puts it: “The progress made in the Civil Rights Era could be rolled back in the guise of machine neutrality … Left unregulated, there’s no kind of recourse if this power is abused.”

Data can be a powerful tool, to hold governments and corporations to account, and with the vast amount of data available there are numerous stories to tell. However with the increasingly central role data and technologies have in every aspect of our lives, we must be mindful that the data we share, whether knowingly or unknowingly, might be used against us.

You can protect yourself from online tracking while disrupting the targeted advertising industry feeding on your online behaviour here and limit your online footprint to keep shady companies away from your data here.

If you want to take action about the ever-growing surveillance industry and you are an EU citizen, there is an ongoing campaign to “Reclaim Your Face”, calling on the European Commission to strictly regulate the use of biometric technologies within the EU. Ideally to prohibit, indiscriminate or arbitrary use of biometrics, which could put us all at risk of unlawful mass surveillance.

From the documentary Coded Bias

ON ACTIVISM

The oath taken at the point of becoming a police constable in England and Wales. Background image: Jenny Holzer’s ‘Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise’.

We're often asked about elements of activism within our collaborative practice as RAKE. Although each of us works separately within different fields of activism, we tend to discover some tension or discomfort when answering these questions. Our shared interests and political engagement are some of the main influences behind the work we make as RAKE - where the themes we address seek to challenge oppressive power structures - but whether our practical outcomes, and visual art in general, can ever really be considered ‘activism’ is something we regularly discuss.

Protest and civil disobedience have a long history of achievement, and so many of the freedoms and privileges we enjoy today are the results of direct action. Despite being criminalised, surveilled, attacked and policed, grassroots movements or events, from the Suffragettes, the Freedom Riders and Stonewall - through to Smash EDO, Extinction Rebellion and Palestine Action, have won vital human rights and environmental victories by purposefully and consciously breaking the law. Of course, when oppressive laws have no moral authority, ‘breaking the law’ becomes legitimate; particularly when some of the worst and most violent atrocities in human history have been legal.

#KillTheBill

It’s no coincidence that the KKK has never been considered a domestic terrorist group by the US government and yet the Black Panther Party was labelled the ‘most dangerous threat to America’ - or that over 1,000 XR activists were recently taken to court (again) while far-right anti-maskers regularly storm London with an inconsistent scattering of arrests. Striving for a better future by challenging the status quo (whether or not nonviolently) has been consistently over-criminalised. Recent events have once again confirmed that activism and people power can be extremely effective; and have highlighted the importance of fighting back against a broken system. In the words of Assata Shakur, “nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them.”.

The Cambridge English Dictionary describes activism as “the use of direct and noticeable action to achieve a result, usually a political or social one”. While political art is usually, by its nature, ‘noticeable’; whether it can be defined as ‘direct’ is another matter. In The Author as Producer (1934), Walter Benjamin makes a distinction between cultural production which is used to express an attitude towards a political situation, and that which takes a position within politics. Banners on the frontline of protests, or ad-hacks on buses and billboards, are effective ways of expressing political opinion to a wide audience - and are certainly ‘noticeable’. But history has shown time and time again that simply expressing political opinion as a standalone act rarely changes anything. Visual art which takes a position within politics is art that actively and directly produces alternatives or affects changes to oppressive institutional structures. Works by Zanele Muholi and Poulomi Basu are examples of visual media made with a strong activist agenda that have enabled real, lasting societal or policy change. However, it is rare to get such powerful results from visual media alone.

Subvertisement via Spelling Mistakes Cost Lives

It can be frustrating for artists who want to translate elements of activism into their visual work to find that, unless they are a member of the community they want to work with, or are personally affected by the pressing need for direct action, this agenda is near impossible; both ethically and practically. However, there are other ways to channel activism into visual expression from a position of privilege. Instead of solely focusing on those affected by injustice and oppression, it’s often more helpful to question the systems that are closer to home; how our own communities, governments or we as individuals are complicit in this suffering. To research, interrogate and visualise the shortcomings, prejudice or violence within our own society - ‘our own backyard’ - can not only be a powerful method of drawing attention to major political imperatives, but also fall within our responsibilities to challenge the very systems that we benefit from.

RAKE strives to actively subvert the ever-shifting boundaries of art as a discipline - and to direct our practice towards, one day, becoming a useful and effective instrument for implementing social and political change - but it’s still important for us as individuals to distinguish between this work and our activism. Visual art has the potential to bring about radical political change; when created in partnership with community organising, people power and other direct forms of action; but not simply as an alternative to these. Direct political action will always be supported and inspired by visual art, but the struggle must be continued on the streets, beyond hierarchical art institutions, for real change to occur.

Follow Sisters Uncut on Twitter

ON RESEARCH

A manual for the Glock 17 pistol

Helga Nowotny (2008), former Professor of Social Studies of Science at the ETH Zurich, defined curiosity as the main driving force of art, causing it to “go beyond the familiar, to explore a space that opens up to the realm of possibilities.”

Research in the arts further encourages practitioners to “go beyond the familiar” by incorporating various approaches, ranging from interrogating theories, exploring different positions and investigating silenced subjects, to experimenting with various tools and using creative approaches to make complex data more accessible. At the core of these enquiries sits the urge to find innovative techniques to engage with a topic - raising questions, encouraging new perspectives and building knowledge.

Professor Estelle Barrett (2014), from the Institute of Koorie Education at Deakin University, describes artistic research as having the “ability to reconfigure our understanding of how knowledge is produced”. It offers to move beyond the limits of knowledge to “transform accounts of the world” (ibid.) – presenting new possibilities of further understanding through the “experimental and emergent nature of its methodologies” (ibid.).

Output from our Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) off to a slow start while processing and learning from images.

According to Hugo Lopez Ortez (2008) “the transmission of knowledge is constrained or facilitated by its medium of presentation”. Building upon this notion, art enables us to expand on forms of representation through interdisciplinary approaches – encouraging the “necessity for ongoing decoding, analysis and translation.” (Barrett and Bolt, 2014)

Because of the great potential of using artistic approaches to carry out and visualise extensive research, the number of artists employing diverse research tools in their practise is rapidly growing. Exemplary is the work of the research group Forensic Architecture, which applies multidisciplinary methodologies, including a variety of technologies and architectural techniques, to “develop an evidentiary system in relation to specific cases” of state violence and violations of human rights. Working closely with NGOs and human rights lawyers, they challenge dubious claims made by corporations, the military, states and police. Through the presentation of these investigations in galleries and museums worldwide, the ground-breaking approaches and sophisticated reconstruction of forensic evidence find access into the artistic realm; making the findings accessible to a wider audience, beyond a specialised group of people.

From the exhibition ‘Towards an Investigative Aesthetics’ by Forensic Architecture at MACBA, 2017

Another example is Laia Abril, a research-based artist utilising various approaches and techniques in her practice, including photography, video, sound and text. In ‘On Abortion’, Abril meticulously investigates and documents the “physical and psychological dangers caused by the continued lack of legal, safe and free access to abortion”. Her multimedia approach, alongside the inclusion of historical and contemporary material, gives insight to a tabooed topic - presenting an encompassing image of abortion.

In our collective work, RAKE has provided us with a space to employ research to explore complex subjects, finding new ways to enquire - using various techniques and methods. For our first project, ‘We May Meet One Day’, we investigated the leak of white supremacist platform Iron March. It was our aim from the beginning to make this complex and abstract set of data more tangible while finding ways for an audience to engage with it. We applied a range of different tools and techniques to visualise information we continued to gather in the process.

Among other approaches, we programmed a map to show the conversation trail between users worldwide; fed user profile pictures to a Generative Adversarial Network to generate the average Iron March user; wrote a program to grab the leaked IP addresses, converting them into physical coordinates, and finally scraped Google Maps for the street views of each of these real-world locations. Making use of various tools and applying different techniques allowed us to visualise specific aspects of the dataset and encourage the audience to further engage with the overarching problem – the rise of far-right ideologies.

Overall, the potential of research in the arts, be it for translating challenging and complex topics, highlighting sensitive issues, or offering new possibilities to inquire, transform and question, is endless. It creates a space that should be continually explored and will definitely continue to sit at the core of the work we create as RAKE.

ON COLLABORATION

From ‘Defensive Tactics Manual’ published by the Northamptonshire Police, 2011

RAKE was formed out of a desire to retain some connection within our dispersing MA group, the wish to build something bigger and more important than ourselves, and also a joke that got out of hand.

It can sometimes feel, or appear, like pure luck that the four of us work easily together without too much friction, having never collaborated together before. But reflecting on the work we’ve undertaken, and in which ways our dynamic has changed or stayed the same over the last year, has provided some insight. It’s both our similarities and differences that make RAKE’s collaboration work; a shared interest in research and investigation-driven projects, alongside a range of different knowledge, skills and ideas, has allowed us to keep the work going to new and exciting places.

The image of the lone genius, once epitomised as the individual intrepid (white, male) photographer, and sustained by the invisible action of countless fixers, drivers, translators, couriers, printers, editors and many others is now fading. Practitioners are recognising that all stages of creative practice - from the making, through critique and experimentation, to exhibition - is a process involving more than any one person. And more than that, that this process itself, whether visible or not, informs work at all stages.

Collaborative/ cooperative/ collective work is built on many different structures; occurring between individuals or groups of artists, between individuals across different disciplines or between an artist and their subject. A shift to socially engaged work, including participatory photography and community interaction, raises further questions of how and when to define collaborations. Many of these structures may also overlap with the existing daily minutia of an artist’s practice, and deciding whether these interactions gain the collaboration label is generally left up to whoever’s holding the pen.

If the lone genius never relied on fearless independence, but selfishness, claiming the support, influence and even work of others for themselves, then the collaborator needs selflessness to put the work and purpose of the collaboration above themselves. How we collaborate matters; how we answer the questions of ownership, authorship and representation that collaboration raises are integral pieces of the process, particularly when working with social or political subject matters. Without answers, collaboration for the sake of collaboration may easily become just a convenient mask for the lone photographer’s last admirers, obscuring whatever power structures remain in place.

RAKE’s collaborative work creates something separate from our individual practices and has allowed us each to relinquish ownership and control, while exploring new subjects and mediums we would not have previously explored in our individual practices. This framework similarly provides the opportunity to move past perfectionism, while leaving the space to openly question and critique the works, visualisations and representations we make. RAKE Community too is an attempt to create and facilitate new instances of this framework, balancing each individual’s skills, ideas, goals, egos and time.

Our collaboration is guided by a joint motivation to push the boundaries of photography and storytelling, to explore the interactions between the visible and invisible, and democratise research and investigation methods. And like investigation, like research, like a camera, or like photography itself, collaboration is a tool. One that we’re still learning to use and still learning about.

RAKE has provided us each a space to keep moving, not only while managing the de(com)pression after the end of an intense MA, but also during the barrage that was 2020. And ultimately, it’s just good to know that even if this shit-show of a government response (apply to your own government where necessary) continues trying to doom us all, at least we can still make some art with our friends... Cue The Beatles.